Educated as a musical performer, composer, and psychologist of music and education, Dr. Larry Scripp is the Founding Chair of the Music-in-Education Concentration at the New England Conservatory and the Founding Director and senior researcher and consultant for the Center for Music and Arts in Education.

A world-renowned former Harvard music researcher, Professor Scripp spent ten years working at Project Zero to investigate artistic development in children.

He has served as Founding Co-Director of the Conservatory Lab Charter School and a Principal Investigator for more than twenty music and arts learning research projects in U.S. public school districts.

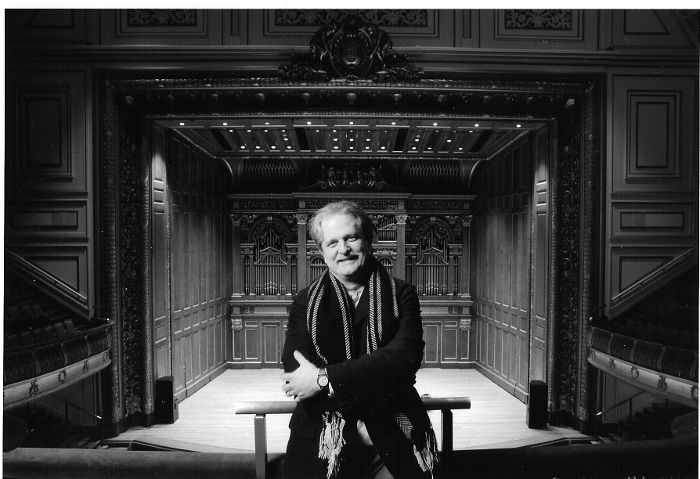

Professor Scripp at the New England Conservatory, where he is the Founding Chair of the Music-in-Education Concentration. Photo credit: Courtesy of Larry Scripp

Professor Scripp at the New England Conservatory, where he is the Founding Chair of the Music-in-Education Concentration. Photo credit: Courtesy of Larry Scripp

Our writer spoke to Dr. Scripp, who is currently the Dean of Music in Education at MindChamps on the role parents play in developing their children’s love for music, and the study behind music and child development.

TNAP: Do you have any advice for parents who want their kids to love and be skillful at music?

Musical education is more than taking them to piano and violin lessons. And music isn’t one instrument. When parents say, “Oh I gave my child a musical education. He had piano lessons,” I say, “No, you gave him piano lessons, but he has to get a little more than that.”

And if I hear, “Well, I gave him piano lessons but I couldn’t get him to practice,” I will reply, “You did not give him piano lessons, you gave him exposure.”

Readers might say, “But they don’t seem to like it.” Well, do what you would do with something very important. Get a new teacher. And if they don’t like the music they’re playing, find another genre.

All kids like classical music. The innovation of Suzuki was to bring simple folk music and classical themes that all children like, provide the properly sized instrument, and insist on parental participation and support.

TNAP: In Singapore, many parents spend a lot of time helping their children with schoolwork. What can parents do to instill music learning at home? Are there any exercises or games that you recommend?

- Participation, attitude, and mindset are very important.

My young daughter loves being chased more than anything else. So I said to her, “If you play that right for four measures, I’m going to have to chase you.”

And she knows it’s a game. It looks like I’m desperate and an ineffective teacher because all I can do is chase her. But you know what? I’m willing to do that. And chasing is a lot better than giving her a lollipop or letting her watch TV for three more hours if she practices more.

So music needs to be its own reward and the more you can get the adrenaline and enthusiasm going, the more effective music lessons and practice will be.

- Praise them for their effort, not for what’s easy for them.

“Wow, how many times did you practice that? Only twice? Well, think of what you can do if you practice it four times.” When it takes more time to get something right, that means you are a really dedicated learner. If it is easy, that means you have already learned to do something.

- Practice alone is not enough.

It has to be accompanied by some sort of vision – a future mindset. So if a child says, “I’m just going to try this out for a couple of weeks and my mother said that if I still like it, I can keep going,” that’s not a strong future mindset.

But if a child says, “Once I learn it, I’ll be doing it for the rest of my life,” that’s a powerful mindset. And it will make a difference.

The latest research shows that if they see themselves in the future doing what they’re doing now—whether it’s learning to read or playing an instrument- they’re going to learn more.

Studies show that if you have people practicing the same amount of time but with very different future mindsets, you will not get the same results.

TNAP: What instrument should you start with?

Piano, violin, and recorder, are very adaptable instruments that have an enormous repertoire. Guitar is good with popular or folk music. Hand drums are good for studying world rhythms.

Don’t start off with more limited instruments like tuba and cymbal – that’s not going to get you a music education no matter what you do. If you want to be a great singer, go and play the keyboard as well as mallet instruments.

Is it enough to just play the drums or the flute? No. Look at the repertoire, the range, and the type of music it plays. If one day a child doesn’t like the flute or bass drum, they’ll be stuck because they’ll have nothing else to do with their music. So learn the fundamental instruments. And always use your voice.

TNAP: Many kids don’t like to practice. What can parents do to help?

Research shows that most children don’t practice regularly unless their parents participate effectively in it. And even the advanced ones go through periods where they dislike practising. All musicians have to face this problem. I did – my children did. It’s normal.

So you should do anything you can to excite your child in learning in general. Be up for the task.

Create expectations and make boundaries. I told my daughter she had to play the piano until she was 16. There should be a push. I said, “Whether you think you like school or not, you’re going. Whether you like to read books or not, you have to read. Whether you like to solve math problems or not, you have to do it. And I’m not going to make an exception for music.”

That’s philosophically secure, and the child will understand that fairness. The interesting thing is, once children learn how to apply their learning to reading books or playing songs together with their friends, they will value the experience for the rest of their lives.

Professor Scripp with his daughter, Miranda, during her early piano lessons at home. Photo credit: Courtesy of Larry Scripp

Professor Scripp with his daughter, Miranda, during her early piano lessons at home. Photo credit: Courtesy of Larry Scripp

Many adults say, “Why did my parents let me quit music when they made me do all this other stuff I didn’t want to do?”

We run into people on the plane or wherever and they talk with real reverence about music, wishing they had learned an instrument or continued playing, or wishing their parents had made them do it instead of allowing them to quit.

So my absolute is: Do not put up with a difficult situation in music education, when you can make it better. Find a good teacher. How do you get a good teacher? Try them out. Get testimonials or reviews. Many people think all music teachers are the same—what could be further from the truth?

TNAP: What would you say to families where neither parents come from a musical lineage, and yet they still want their child to learn music? If the parents are unable to demonstrate how to play, is there any way for them to help their child with music other than learning it themselves?

You can sit down and ask the child what they’re learning, and demonstrate it. Ask them, “Can you play this piece in your music book?”

Or comment, “I looked on the sheet from your teacher and it says that you’re supposed to play a scale frontwards and backwards. Is that hard to do? Can you show me how you learned to do it?”

You’re participating in their learning when you get them to demonstrate what they have learned. And at some point they might even ask the parent, “By the way, can you do this?” You say, “Well I can try but don’t be too hard on me for doing it wrong.” That’s how music learning can become a very productive game.

I have a rule: When it comes time for your child’s musical performance, the parent should never convey that anything they do is wrong. Just praise them for being out there and demonstrating their learning. But when it comes to practice, then ask questions that will lead to improvement.

TNAP: Can you talk a little about music’s effect on social-emotional development?

Music is social and performance generally is social. Because I work in school assessment, I test students’ social-emotional development skills. The classic ones are things like empathy. Music empathy actually means playing together.

If you can stay on the same beat together or sing and play in tune with another person, that’s a form of empathy.

There’s also conflict resolution and interpretation. I’m hearing what you’re doing while I’m doing what I’m doing—are we doing the same thing, and how do we feel about it?

Emotional means dealing with frustration. At some point, you sit down with your child like we did our 11-year-old daughter and say, “Look, you’re not going to be able to do this unless you really want to do this. We can teach you anything we want, but now that you’re 11, you’re going to have to want it.”

Teaching yourself and teaching others is a social-emotional skill.

Some parents say, “My child is very good at the violin and I don’t want him playing with other children who aren’t very good.”

And you’re like, “You mean you’re in a situation where you don’t teach each other? Or work and practice with each other?” And they say no, that’s a waste of time. But at the New England Conservatory, there are many professors who say in the last stages of your career as a conservatory student, you have to teach other people to get to the best level.

TNAP: Are there studies to show that certain songs or types of music help to improve a child’s concentration or academic achievements? For example, playing classical music to babies.

I believe parents should be very confident that their children’s musical studies will have a positive effect on their brain growth, cognitive development and related academic skills.

The Mozart Effect showed that when you listen to a piece of classical music for a short period of time, it can improve test-taking skills but only for a short period of time. Followup studies show that you don’t get consistent effects from music study unless you start to participate in music-making regularly.

Other studies have measured music’s impact on brain development in non-musicians versus amateur musicians versus professional musicians.

And when you see that the brain density, cognition placement or imagery is different for all three and it’s consistently more with the amateur or professional musicians, we can now say that the degree of musical engagement, the process, length of practice, and expert teaching is the most important effect of music education on brain capacity.

Not the exposure. Not just listening. And don’t worry, the effect begins early in childhood, so not every child has to become a professional to enjoy the benefits of music in their education.

By Jenny Tai.

* * * * *

Like what you see here? Get parenting tips and stories straight to your inbox! Join our mailing list here.

Want to be heard 👂 and seen 👀 by over 100,000 parents in Singapore? We can help! Leave your contact here and we’ll be in touch.

Leave a Comment: