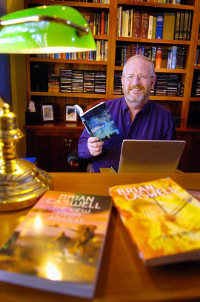

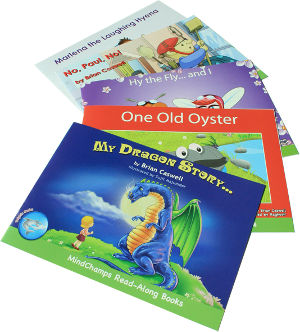

Brian Caswell is the Dean of Research and Program Development at MindChamps. An internationally-acclaimed award-winning author and a respected educationist with thirty years of experience in the areas of public and private education, he has been in constant demand as a speaker and literary consultant. Brian is also one of Australia’s most innovative thinkers and an acknowledged expert on today’s youth and their response to the modern environment and the demands of the school system, as well as the link between the development of students’ creativity and academic success.

In the last part of our interview series, The New Age Parents spoke to Brian Caswell to learn more about reading for young children, and how parents can make reading fun and exciting.

On the biggest misconception on reading

People make a huge mistake about reading. They think reading is making sounds. So as long as the child can make a sound when they see a symbol, they think they can read. In fact, reading is not about that. That is about 20% of reading, which is phonemic awareness.

All the research and the experts come down to the same thing. Some people say five; some say there are seven aspects to reading. One is phonemic awareness, now that’s not phonics. Phonic is being able to hear sounds. That is a neurological function of a child in his early years. So your auditory template, the matrix in your brain is developing from about 3 months before birth, through to about 4 to 5 years old. In that time, what are the sounds are heard and mastered, will be available for the rest of your life, for you to use.

If you don’t hear those sounds, by the time you get to about 4 – 5 years is the key period. But it actually stretches to about 10 or 11, if you have not heard those heard sounds and mastered them by 11 or 12, there is a very big chance that you will never be able to hear them at all. That may sound strange. I’ve got ears, but it’s not about how those sounds rattle these little bones in your ear, it’s about whether you have a neuro-connection between that and the auditory cortex that can store that sound, and then recognize when it hears it. If it was never heard during that critical period, you can’t ‘hear’ it after that.

So I’m never ever going to speak mandarin without an accent because I can’t hear all the tones. You see in Chinese, the same word can have four different tones. I don’t understand it. The fact that I can’t hear the difference means that I am never going to be able to master the language at the level it needs for mastering. I can come pretty close but if you learn a language after the age of 12, you can’t learn it without an accent. Unless there is an incredible amount of effort put in. I mean, severe, you know you got to re-program your brain and that takes an immense amount of effort. It’s possible. There are people who have lost their accents over time. But only because they worked so hard at it. Actors do it.

The second is phonic awareness. Being able to see shapes or symbols and tie them to a sound. This is only 20% of reading, but people make this component the 100% of reading, which is not. There are other aspects like comprehension. You see every language has its own rhythms, and part of our jobs in training the child to read is to train them to recognize the rhythms of the language. The rhythms of written language are different to the rhythms of spoken language.

That’s an interesting point. How are the rhythms of the spoken language different from the written language?

Literary language is different to spoken language. It has its own syntax; it has its own way of flowing. There are lots of big overlaps, but they are different forms of English. The way we speak is not the way we write, and the way we write and the way we read what we write is not necessarily the way we speak.

The two things which I think are most important that are neglected more than any other are one; understanding the structure of the language. How sentences fit together, how they work, an intuitive feeling for when a sentence is correct, and when it’s not. And this is not about the knowledge of grammar. I am talking about experiencing language to such an extent that you know when the flow is right, whether the sentence is working, or it’s not. And that is not something you can teach easily in a lecture situation. That is experiential; you learn that by experiencing it, which is practically how young children learn everything. You can’t teach a young kid by telling them what to experience. They got to live it.

This is why when we talk about immersive reading, we talk about what the story and book are about, instead of starting off with elements like the letters, the blends and the sounds. And all it consists of is sitting down with the child, making the child warm comfortable, content and happy and then just having a whole lot of fun with books. Reading them, putting on voices, getting them to predict what’s going to happen next. This is before they can even decipher the text. So that a book becomes the most important fun thing they can do.

So when you go into my son’s house, for example, his kid will run up to you with a book in his hand and say, “Let me read this book to you!” He can’t read, he’s four. But what he does is he opens up the book and he recites the whole story, because he has experienced that book maybe twenty or thirty times, and because he loves it. And so, he has learned the book.

But he doesn’t understand what he is reading. How does that help?

It doesn’t matter if he is reciting something, or that he is not decoding it, because that book is alive for him. He loves predicting, he loves looking at the pictures, and he loves what is happening in the pictures. All of those things have got him to the point where books are really really important to him. So when he comes to school, and he begins phonics as part of his learning process, he will devour the phonics because he can read the books himself. The books are so important to him, he is going to learn that, he’s got a purpose, he’s got a reason. And the phonics will come to him almost instantaneously because he is already making the connections; he is learning it through experience and not lecturing.

If they enjoy it, they are going to go and revisit that memory as often as possible, because they get a good feeling. But if it’s stored with frustration, confusion, anger and fear, “I don’t want to feel those things, so I am not going to go back and visit it.” That’s where you get a reluctant reader.

I read about 8 -10 books a week when I was 12 years old, right through my teen years. Because I loved reading. Why do I love reading? Because when I was a child, my parents were very poor when they got married and we lived in the hills in the North Wales of UK. We had no books, the village we lived in had no books, no library. And my parents couldn’t afford to buy books. So what my mother used to do is to write her own books during the day, and read them to us at night. So she created a cast of characters who came back in different stories and we knew them, and we were involved, we would be predicting them.

So I grew up at a very young age with books being this focus of fun, but I also grew up believing that stories were something you created and shared, not something you borrow or buy from someone else. The idea of being a storyteller was built in me from the very beginning because stories were things you wrote and shared, that you read together and that they were fun.

To read his previous interviews, go to:

– Exclusive interview with Brian Caswell

– Learning And Education In The 21st Century

– Defining and Enriching Your Child’s Creativity

* * * * *

Like what you see here? Get parenting tips and stories straight to your inbox! Join our mailing list here.

Want to be heard 👂 and seen 👀 by over 100,000 parents in Singapore? We can help! Leave your contact here and we’ll be in touch.

Leave a Comment: